Key takeaways

-

There is wide variation in genetic screening for cardiomyopathy among centers.

-

In this study, only half the children with cardiomyopathy had undergone genetic screening.

-

Cardiac surveillance of first-degree relatives of children with cardiomyopathy is strongly recommended.

Research background: pediatric cardiomyopathy and genetic causes

Cardiomyopathy is a rare disease that causes the heart muscles to deteriorate, leading to an insufficient amount of blood reaching the heart. In children, the disease can lead to significant morbidities and even mortality.

There are five phenotypes of cardiomyopathy:

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)

- Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM)

- Left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC)

- Arrhythmogenic ventricular cardiomyopathy (AVC)

Current consensus guidelines recommend:

- Genetic testing for children and adults with cardiomyopathy

- Cardiac surveillance in first-degree relatives

- Genetic testing for a known familial variant in first degree relatives

Barriers to pediatric genetic testing include:

- Financial factors related to reimbursement

- Family understanding; perception of testing

- Limited data to guide physician practice for pediatric cardiomyopathy

- Variations in pediatric genetic testing not well studied

Despite the diverse types of cardiomyopathies found in children, genes that encode sarcomeric, cytoskeletal or desmosomal proteins are important causes of the disease among all ages. Still, data related to genetic testing in children remains limited and there remains a variation in clinical testing practices.

Previous research lacked significant findings such as a large and diverse sample size, identifying barriers to treatment, and other important factors for diagnosis and treatment.

The Pediatric Cardiomyopathy (PCM) Genes study was established to perform exome sequencing in a large prospectively recruited cohort.

Study goals:

- Develop approaches to exome analysis for autosomal dominant disease

- Determine genotype-phenotype correlations

- Identify genetic modifiers influencing the long-term clinical course of children with cardiomyopathy

Melanie Everitt, MD, director of Pediatric Heart Transplant at Children’s Hospital Colorado, and one of the study co-authors participates in the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry investigator group to understand how to improve outcomes for children with cardiomyopathy so they can live longer, fuller lives without heart transplant.

The first results of the study included:

- Determining prevalence of pathogenic variants in known cardiomyopathy genes

- Investigating associations between the phenotype and demographic factors

- Identifying practice variation in genetic testing of children with cardiomyopathy

Research methods: phenotypes, health data indicators of pediatric cardiomyopathy

Patients

- Enrollment period: 2013 to 2016

- Network: 14 North American institutions participating in Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry

- Eligibility:

- Diagnosis of idiopathic or primary cardiomyopathy with a phenotype of DCM, HCM, RCM, LVNC or presumed myocarditis before age 18

- Biological parent or affected relative of eligible patient

- Exclusions: cardiomyopathy caused by another condition, such as neuromuscular disorder or genetic syndrome

- Data collected included:

- Cardiac phenotypic data

- Demographic information

- Anthropometric measurements

- Family history with pedigree

- Heart failure class

- Results of cardiac studies (echocardiograms, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, ECGs, Holter monitoring and endomyocardial biopsies)

- Cardiac transplant status

- Cause of death (if child died)

Sample collection, preparation and sequencing

Blood and saliva samples were collected from patients and analyzed, and DNA was extracted. The DNA then underwent exome sequencing and alignment.

Variant assessment

In total, 37 genes were selected for pathogenicity testing based on their history of causing cardiomyopathy in children from clinical cardiomyopathy genetic testing panels. The TTR gene, which has not traditionally shown as an indicator for the disease, was included because of its potential to be a modifier.

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact, chi-squared tests and logistic regression were used to analyze the differences between cardiomyopathy phenotypes.

Research results: genetic factors that cause cardiomyopathy in children

Table 1. Cardiomyopathy-Causing Genes Analyzed in the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Genes Study

| ABCC9 | LAMP2 | NEXN | TNNC1 |

| ACTC1 | LDB3 | PLN | TNNI3 |

| ACTN2 | LMNA | PRKAG2 | TNNT2 |

| ANKRD1 | MYBPC3 | RBM20 | TPM1 |

| BAG3 | MYH6 | SCN5A | TTN |

| CAV3 | MYH7 | SCO2 | TTR |

| CRYAB | MYL2 | SGCD | VCL |

| CSRP3 | MYL3 | SURF1 | |

| DES | MYPN | TAZ | |

| EMD | NEBL | TCAP |

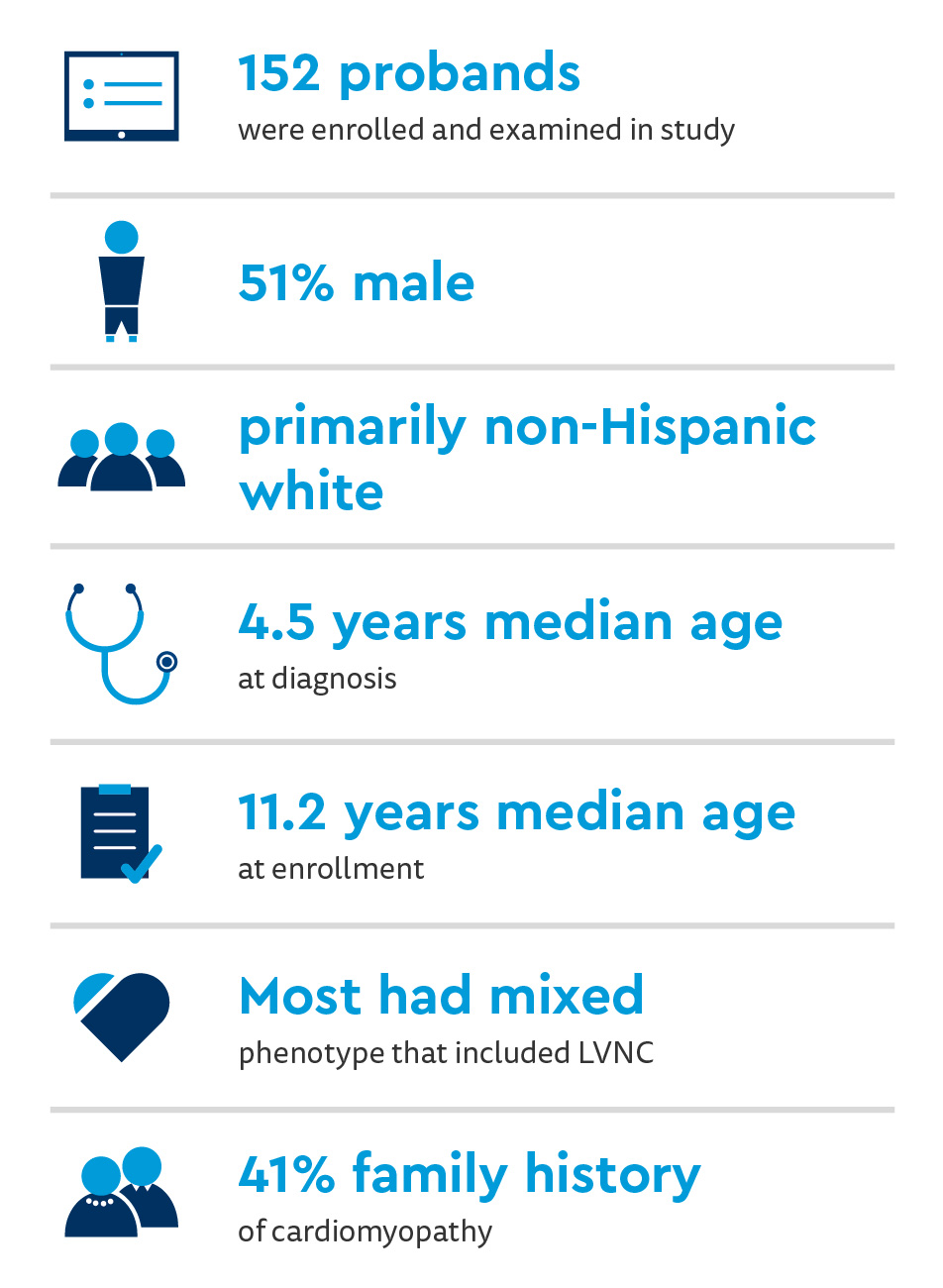

PCM genes participants

Age and sex differences noticed between cardiomyopathy phenotypes:

- Children with HCM have a higher median age at diagnosis than most other phenotypes (P=0.0004)

- Males (71%) had higher diagnostic rates of the HCM phenotype than females

- HCM showed the highest rates of a positive family history (67%)

Clinical genetic testing practices and outcomes:

- 81% of participants had cardiomyopathy gene panel

- Eight participants excluded (had other types of genetic testing)

- Children with testing had higher rates of a positive family history (51%), specifically, children with HCM (67%)

- Children with HCM more likely to undergo testing (74%)

- Positive results from clinical cardiomyopathy gene panel testing were higher in children with HCM (68%)

Sequencing results: (89% of participants’ diagnoses confirmed by exome sequencing)

- 32% “positive” or “likely” pathogenic finding

- Familial diagnostic yields:

- 35% DCM

- 43% LVNC/Mixed

- 68% HCM

- 75% RCM

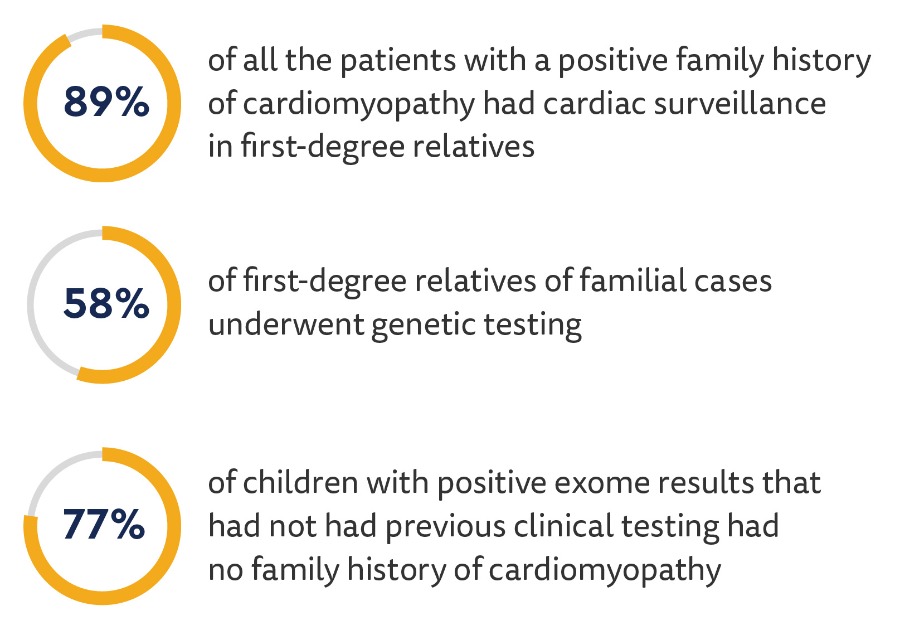

Cardiac surveillance and genetic testing in family members:

Research discussion and conclusions: routine genetic testing for familial, idiopathic cardiomyopathy

This large-scale study attempted to establish disease-specific genotype-phenotype equivalents in pediatric cardiomyopathy and current guidelines and clinical testing practices. Multiple diagnostic yields for cardiomyopathy were identified, specifically for broad, inclusive genetic testing in children with familial or idiopathic cardiomyopathy.

Key findings:

- Cardiac surveillance of first-degree relatives of children with cardiomyopathy is strongly recommended.

- HCM (28% vs. 42%) was less common in this study than previous ones.

- Those with LVNC/Mixed cardiomyopathy had higher rates of a family history of cardiomyopathy than other phenotypes.

- Although genetic testing is more commonly used, the ways it is used are highly varied – ranging from 0% to 97% of patients having undergone it.

- First-degree relatives had a cardiac screening in 42% of idiopathic cases, showing that there could be an underestimation of the actual prevalence of the condition in family members.

- The study identified pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in 32% of child participants.

- There was a significant association between family history as a genetic cause for cardiomyopathy and clinical genetic testing.

- Pathogenic variants were identified in 36% of children with idiopathic HCM and 50% of idiopathic RCM participants.

Overall, the results showed that a genetic diagnosis could be made in most children – especially those without a previously documented history of cardiac problems. Genetic testing is recommended for both familial and idiopathic cardiomyopathy.

Future studies should strive to enroll children with the LVNC/Mixed cardiomyopathy phenotype and examine the motivations and barriers to genetic testing for pediatric cardiomyopathy for patients. A longitudinal study design, variant interpretation and new approaches to predict variant effect should also be considered.

Featured researcher

Melanie Everitt, MD

Director of Pediatric Heart Transplant

The Heart Institute

Children's Hospital Colorado

Professor

Pediatrics-Cardiology

University of Colorado School of Medicine

720-777-0123

720-777-0123