- Doctors & Departments

-

Conditions & Advice

- Overview

- Conditions and Symptoms

- Symptom Checker

- Parent Resources

- The Connection Journey

- Calm A Crying Baby

- Sports Articles

- Dosage Tables

- Baby Guide

-

Your Visit

- Overview

- Prepare for Your Visit

- Your Overnight Stay

- Send a Cheer Card

- Family and Patient Resources

- Patient Cost Estimate

- Insurance and Financial Resources

- Online Bill Pay

- Medical Records

- Policies and Procedures

- We Ask Because We Care

Click to find the locations nearest youFind locations by region

See all locations -

Community

- Overview

- Addressing the Youth Mental Health Crisis

- Calendar of Events

- Child Health Advocacy

- Community Health

- Community Partners

- Corporate Relations

- Global Health

- Patient Advocacy

- Patient Stories

- Pediatric Affiliations

- Support Children’s Colorado

- Specialty Outreach Clinics

Your Support Matters

Upcoming Events

Colorado Hospitals Substance Exposed Newborn Quality Improvement Collaborative CHoSEN Conference (Hybrid)

Monday, April 29, 2024The CHoSEN Collaborative is an effort to increase consistency in...

-

Research & Innovation

- Overview

- Pediatric Clinical Trials

- Q: Pediatric Health Advances

- Discoveries and Milestones

- Training and Internships

- Academic Affiliation

- Investigator Resources

- Funding Opportunities

- Center For Innovation

- Support Our Research

- Research Areas

It starts with a Q:

For the latest cutting-edge research, innovative collaborations and remarkable discoveries in child health, read stories from across all our areas of study in Q: Advances and Answers in Pediatric Health.

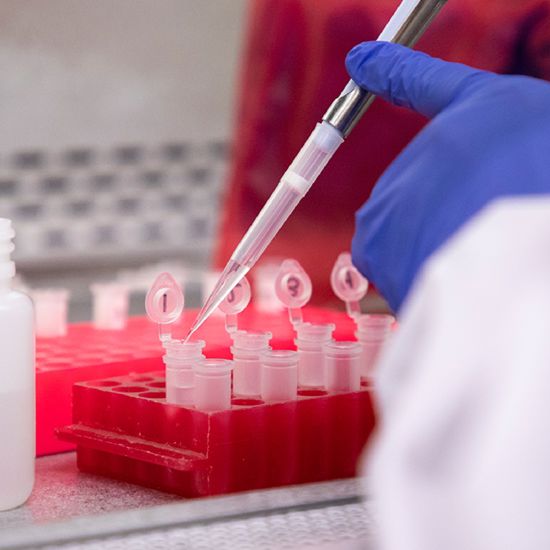

Our Pediatric Research

At Children's Hospital Colorado, our goal is to improve healthcare technology and infrastructure, while inspiring the next generation of leaders in pediatric medicine.

THIRD

NIH-funded Department of Pediatrics in the nation*

40+

Years dedicated to research and innovation

Child health research is at the core of our commitment to deliver the best clinical care for kids. During the research process, our scientists study the genetic, biologic and cellular mechanisms of disease, injury and repair. The discoveries from these studies are then translated into improved diagnostics and treatments, providing cutting-edge therapies to our patients. Armed with new answers to the problems our patients face, we're constantly adapting our bedside protocols to deliver the best care.

By prioritizing and advancing research, education, clinical work and process improvement, we're speeding the integration of our discoveries into the clinical engine, helping patients in new and innovative ways.

It starts with a Q:

For the latest cutting-edge research, innovative collaborations and remarkable discoveries in child health, read stories from across all our areas of study in Q: Advances and Answers in Pediatric Health.

Key focus areas

Looking for outcomes from a research study?

If you or your child participated in a research study at Children's Colorado, please visit ClinicalTrials.gov for information regarding the outcomes. ClinicalTrials.gov is intended under law to provide complete results and enhance patients' access to the findings of clinical trials.

If you can't find what you're looking for, please contact the primary investigator or your doctor at Children's Colorado.

*Third highest funded Department of Pediatrics in the nation according to the Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research.

720-777-0123

720-777-0123