In traditional cancer models, researchers might culture malignant cells and see how they respond to various treatments.

"You can't really do that with craniopharyngioma," says Todd Hankinson, MD, a pediatric neurosurgeon in the Neuroscience Institute at Children's Hospital Colorado.

Unlike some more aggressive brain cancers, craniopharyngioma cells are slow-growing and biologically diverse, and have proven almost impossible to culture.

Reviewing the consistency of craniopharyngioma cell location

Their location, however, is remarkably consistent. They form behind the eyes and grow upward, impacting the optic nerve, the pituitary gland and the hypothalamus — and often cause blindness, endocrine imbalances and morbid obesity. That's in addition to potential brain artery damage, memory problems and hydrocephalus.

"We're pretty good at controlling these tumors with surgery and radiation,” says Dr. Hankinson. "These children usually don't die. But they live with substantial problems for a really long time. One study showed they have the worst quality of life scores of any pediatric brain tumor there is."

They're also difficult to study because they're composed of several parts. There's a solid mass and often a faster-growing cystic component. Some structures resemble brain tissue, while others look more epithelial. Doctors aren't sure which of these components drive tumor growth, and there's currently no treatment on the market to mitigate it.

Advancing treatment for pediatric craniopharyngioma

That may soon change. Five years ago, Dr. Hankinson started Advancing Treatment for Pediatric Craniopharyngioma, a 13-center consortium devoted to just that, thanks to funding provided by The Morgan Adams Foundation Pediatric Brain Tumor Research Program.

Working cooperatively and in conjunction with a group in London that developed the first and only animal model of the disease, the consortium is currently conducting several studies to identify patterns of gene expression and protein activity that might drive tumor growth.

"With that info, we can look at databases to determine if any existing medications target a pathway uniquely expressed in craniopharyngioma," Dr. Hankinson says. "If there are any, we can call up our friends in London and say, 'Hey, there's a drug out there that's safe in humans; take your animal model and see if it works.' We're at varying stages of this process right now with four or five different drugs."

If any one of those drugs does work — and they all show promise — it would be the first ever to treat the underlying mechanisms of the disease. And right now, there's little competition.

"We're the only consortium in North America doing work like this."

— Todd Hankinson, MD

Featured Researchers

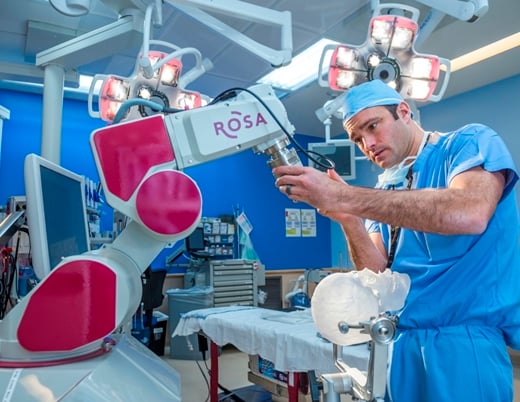

Todd Hankinson, MD

Division Head

Pediatric Neurosurgery

Children's Hospital Colorado

Professor of Neurosurgery and Pediatrics

University of Colorado School of Medicine

720-777-0123

720-777-0123