Can a team of pediatric heart researchers identify why some children's hearts fail after single ventricle surgery and identify potential therapeutic drugs to stop that progression?

A team of doctors at Children’s Hospital Colorado’s Heart Institute is working to uncover the exact mechanisms that lead to heart failure for some children after single ventricle surgery. The hope is to not only identify potential drugs to slow the progression, but ultimately prevent the need for a heart transplant all together.

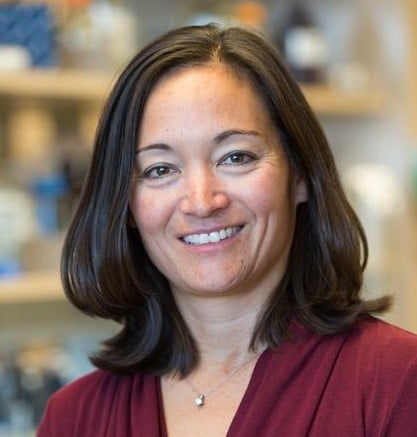

The University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus is home to one of the largest IRB-approved cardiac tissue biobanks in the country, where Shelley Miyamoto, MD, and her team receive freshly explanted heart tissue to study. This area of pediatric research is particularly valuable because what we know about heart failure in adults is vastly different than what we know about heart failure in children. As Dr. Miyamoto puts it, “There’s something different about pediatric heart failure,” and the team at Children’s Colorado is determined to figure out what.

One of the most common severe congenital heart diseases is single ventricle disease, where a baby is born with only one pumping chamber of the heart. The most common treatment path for single ventricle babies is a series of three surgeries over the first five years of the child’s life to reroute the heart’s blood flow. After the third surgery, known as the Fontan procedure, an entire team of experts in the Children’s Colorado Fontan multidisciplinary clinic partner with the child’s primary cardiologist to support the child through the next hurdles. The team watches for complications in the lungs and liver, tests for neurodevelopmental issues and monitors patients for the signs of heart failure that could require an eventual heart transplant.

Dr. Miyamoto and her team are working to understand why heart failure happens to these young children. She has spent nearly two decades at Children’s Colorado and is the top-funded child health research investigator at the Heart Institute. She is also a valuable mentor to Anastacia “Tasha” Garcia, PhD, Stephanie Nakano, MD, and Kathryn Chatfield, MD, PhD, among others. Together, they are making significant contributions to this area of research.

The link between single ventricle heart disease and mitochondrial dysfunction

When Dr. Garcia arrived at Children’s Colorado nearly eight years ago, Dr. Miyamoto saw an opportunity to bridge the world of basic science and clinical translational research for single ventricle heart disease. At the time, researchers knew that adults with heart failure typically have mitochondrial dysfunction, where the energy factory of the cells is not functioning properly. But that was never proven true for single ventricle pediatric patients — until now.

“Until recently, very little was known about the transition to heart failure in this unique population,” Dr. Garcia explains. “But over the past several years, our lab and others have really characterized what happens at a molecular level.”

Dr. Garcia has worked her entire professional career to identify mechanisms of heart failure progression and to assess if there is mitochondrial dysfunction in these failing single ventricle hearts. And according to Dr. Miyamoto, Dr. Garcia’s latest paper, published earlier this year in Journal of the American College of Cardiology, is the first to show proof of this. Her team found that failing single ventricle hearts have dysregulated metabolic pathways and impaired mitochondrial function. They also found an intermediate metabolic phenotype in single ventricle hearts prior to the onset of heart failure, suggesting even nonfailing single ventricle hearts are vulnerable to metabolic dysfunction and eventual heart failure.

Preparing for mitochondrial research studies

These kinds of studies are possible thanks to the cardiac tissue biobank on the CU Anschutz Medical Campus. This is an essential tool for pediatric researchers studying heart failure because they are not able to conduct many of the invasive studies researchers perform to study heart failure in adults, such as heart muscle biopsies. Once a child needs a heart transplant, the researchers get permission from the families to take part of the diseased heart for this biobank. The challenge with mitochondrial studies like the one Drs. Miyamoto and Garcia have been working on is timing.

“These mitochondrial studies have to be done in the moment, because once you freeze the mitochondria, they burst and they aren’t going to function anymore,” Dr. Miyamoto says. “Some of these studies need to be done in the middle of the night or the middle of the week. If it’s Christmas Day, it’s done on Christmas Day.”

Once the team is notified that a heart transplant is taking place, they spring into action to complete their mitochondrial studies immediately, they then freeze the rest of the heart tissue to study later.

“That freezes that piece of tissue in time. So, it preserves things like enzymes, proteins and genes so we can go back and look later,” Dr. Miyamoto says.

Mitochondrial function as a therapeutic target

With this understanding of the mitochondria’s role in heart failure for single ventricle patients, Drs. Miyamoto and Garcia and their team have turned to studying different, promising therapeutic options that target the mitochondria’s function.

“This is highly impactful, because there are now drugs that target the mitochondria,” Dr. Miyamoto explains. “If this is one of the reasons the heart is failing, then there are therapies that can target that mitochondria and hopefully help the mitochondria function better.”

Along with their collaborator, Denver Health’s head of cardiology Brian Stauffer, MD, Drs. Miyamoto, Garcia and Chatfield have identified the drug elamipretide (which is not yet FDA approved for any indication in the U.S.) as a helpful option to improve mitochondrial function in a failing heart. In addition to this drug, Dr. Miyamoto’s current R01 grant is looking into a drug called sildenafil, which could also improve mitochondrial function in this population.

“We need to think about different targets of therapy and identifying different drugs that work in our [pediatric] population and not just assume that all these drugs that are great for adults with heart failure are going to help children,” Dr. Miyamoto says.

The location of Children’s Colorado on a major medical campus with researchers studying the entire lifespan on all corners of campus offers a unique opportunity for collaboration. Dr. Miyamoto says all this work would not be possible without the valuable collaboration with adult cardiology colleagues on the CU Anschutz Medical Campus who started this group with her back in 2007: Kika Sucharov, PhD, a molecular biologist and Dr. Stauffer. Dr. Chatfield is also on the pediatric team as one of Dr. Miyamoto’s mentees, and she is an expert in cardiac genetics and mitochondrial function, who plays a key role in bringing these research studies to life. She has also been essential to the team’s research on the drug elamipretide and mitochondrial function over the years.

Advancing heart disease research

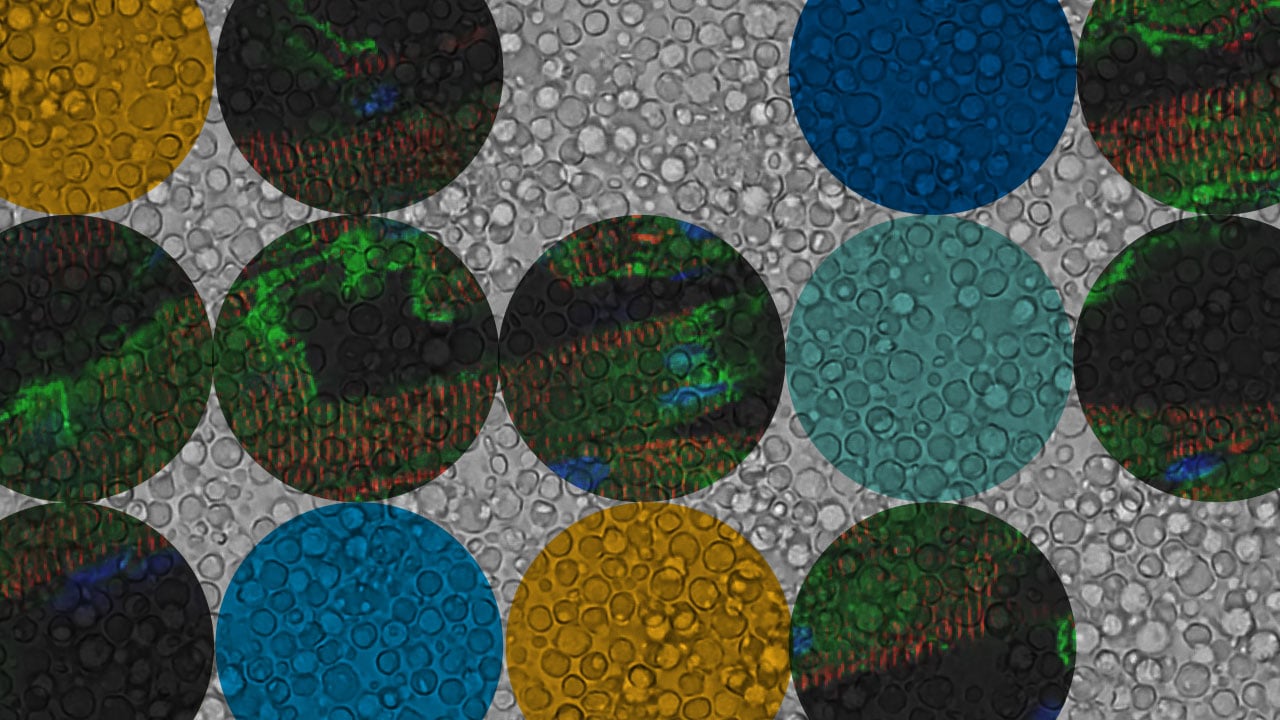

Pediatric cardiologist Dr. Nakano collaborates closely with Drs. Miyamoto and Garcia and is continuing to push this research forward with a $2.4 million award from the Department of Defense (DOD) to study a specific kind of single ventricle heart disease, hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). HLHS is a condition where the left side of the heart is underdeveloped and nonfunctional. This study generates heart muscle cells from circulating white blood cells in HLHS patients, known as human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes.

Dr. Nakano will explore three different areas with the DOD’s Investigator-Initiated Research Award funding. The first area is focused on better understanding the changes in HLHS heart muscle cells that predispose them to failure, which could ultimately help delay or erase the need for a heart transplant. Next, the study will investigate the effects of having low oxygen levels for an extended period of time, as many single ventricle patients are exposed to low oxygen for the first years of their life. The third part of this research will test various drug therapies by screening thousands of potential compounds to see if any improve heart muscle cell contraction.

Over the years, these Heart Institute doctors have shifted their work together from a mentor-mentee relationship to now researching side-by-side to advance this research.

“They are brilliant scientists,” Dr. Miyamoto says about her colleagues. “I get more joy, and I’m more proud of the success they have than my own success. It just feels so much bigger to me.” Their collaborative efforts are accelerating our understanding of why and how these young hearts fail for the smallest patients.

Featured Researchers

Shelley Miyamoto, MD

Chair of Pediatric Cardiology, Co-Director of the Heart Institute

Children's Hospital Colorado

Section Head of Cardiology, Department of Pediatrics

Pediatric Cardiology

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Stephanie Nakano, MD

Advanced heart failure and transplant cardiologist

The Heart Institute

Children's Hospital Colorado

Associate professor

Pediatrics-Cardiology

University of Colorado School of Medicine

720-777-0123

720-777-0123