Hunter Peters' spine looked more like the toy model of a twisting roller coaster track than a 3-year-old's backbone.

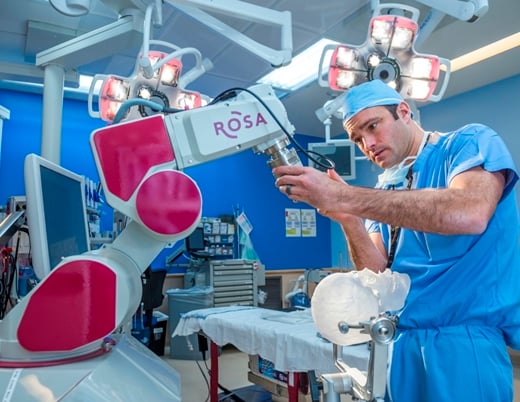

Sumeet Garg, MD, pediatric orthopedic surgeon at Children's Hospital Colorado, holds a 3D model of it in his palm, demonstrating the significance of the 90-degree-plus curve.

"That's definitely pushing it," Dr. Garg says, turning it in his hand, examining the complicated twists. "That's as small as we could probably go."

To imagine operating on a spine that small is daunting, and some hospitals might not have done it. Because of Hunter's small stature, the risks for bleeding, paralysis and infection were big, especially because the spinal cord was being compressed. A spine that small often can't support the screws needed to stabilize the spine for reconstruction. Surgeons prefer to let kids grow bigger before operating.

But Hunter's spine was compressing his spinal cord. Dr. Garg and his colleague, pediatric neurosurgeon Todd Hankinson, MD, didn't have the luxury of imagining what this surgery would be like when he was bigger. Hunter's legs were rapidly weakening, and he was nearing the very real possibility of lifelong paralysis. There was no more time.

"When you see your kid losing the use of his legs, you've got to do something about it if there's something you can do," Hunter's dad, Jeff Peters, says.

"It was a really hard decision," says his mom, Jennifer Peters. She looks at Jeff.

"Because you know that you're risking your child's life," he finishes.

Pierre Robin sequence and congenital kyphoscoliosis

When Jennifer was pregnant with Hunter, her physicians at a Denver hospital suspected he had Pierre Robin sequence, a set of face and head abnormalities such as a smaller lower jaw, cleft palate and breathing trouble that present at birth.

The night before birth, physicians took an X-ray and noticed a curve in the baby's spine — another, rarer abnormality of Pierre Robin sequence — but there were bigger things to worry about, like ensuring respiratory stability after birth.

After six weeks in a neonatal intensive care unit, Jeff and Jennifer brought Hunter home. Jennifer noticed the bump in Hunter's back, but with the reassurance of his caregivers, didn't worry about it. When Hunter was about 5 months old, the bump became more prominent. Suddenly, its growth progressed.

"It felt like, month-to-month you could see a physical difference in him," Jeff says. "It was fast. It was unbelievably fast."

Doctors at their local hospital diagnosed him with congenital kyphoscoliosis, or curvature of the spine in two planes. As standard treatment, Hunter's physicians put him in a spine cast that encased his trunk, extending from his shoulders to his waist, to slow his spine growth and delay surgery.

One day, while wearing the cast, Hunter choked, aspirated and lost consciousness. As paramedics worked to revive him, Jeff frantically tried in vain to cut off the cast with large shears. In the Denver Health emergency department — a Level I trauma center — someone finally managed to remove it.

It was a breaking point for Jeff and Jennifer.

"We decided that we wanted to change directions," Jeff remembers. "It's something I don't even like thinking about, coming that close to losing him. But it forced us to do something else."

They reached out for second opinions and eventually ended up at Children's Colorado.

"From that point forward, everything changed for the better," Jeff says.

Preparing for spinal fusion surgery with a model of Hunter's tiny spine

Drs. Garg and Hankinson showed the Peters the 3D model of Hunter's spine, to explain to them how the spine was compressing the spinal cord, and that paralysis was a possibility without treatment.

"A big part of the planning is talking to the families about it upfront." Dr. Hankinson says. "It's much easier for the parents to understand how we got here, when the time comes."

"The surgery itself could paralyze him," Dr. Garg adds. "It was very high risk because there's a lower margin for error due to his small size and already compressed spinal cord. It's the biggest surgery we do."

"One of the great things about working with Dr. Garg was how refreshingly straightforward he was to us about Hunter's situation," Jeff says. "He was really upfront and honest about it."

"Which made it easier for us to make these decisions," Jennifer adds.

Although Hunter was in good neurological shape when he arrived at Children's Colorado, less than a year later — just before his third birthday — he was dragging both feet when he walked with a walker. His reflexes were worsening.

Drs. Garg and Hankinson weighed the situation. Dr. Hankinson stared at the spine model on his desk for about a week, contemplating the best surgical approach. They talked through their concerns, asking if the screws were safe. Would it structurally benefit him? Was it too much of a risk for potentially no reward?

Drs. Garg and Hankinson practiced the operation on the model, using custom guides to help them precisely insert the screws.

"We sat down with the people from the company that makes the guides, with our 3D model, and fit every single guide to make sure they would fit the way we wanted them," Dr. Hankinson said. "They took them and had them sterilized so we could use them in the OR."

"That is such a huge level of comfort that this isn't the first time they're going to see it," Jeff says, describing the surgeons' preparation for operating. "It's not the first time that they're even going to do it. It's that they're actually going to take the time to trial and error to eliminate some of the risks involved."

Hunter's spinal fusion surgery

"When we checked in that morning, the nurse looked down the roster and said, 'Wow, you guys got the A team,'" Jeff recalls. "Jen and I looked at each other like —"

Jeff and Jennifer exchange raised eyebrows and smiles, Jeff's fist in the air.

That day, they spent 10 hours in the waiting room with family and friends, receiving hourly updates from the OR nurse. It was going well, but it was going slowly.

It started with Dr. Garg and Molly Buerk, PA-C, Dr. Garg's physician assistant, exposing Hunter's spine. To complicate matters, Hunter had no baseline signals from his spinal cord monitoring due to the compression of the cord.

After exposing Hunter's spine, Dr. Hankinson joined the surgery. Standing on either side of the operating table, Drs. Garg and Hankinson placed the screws in the spine. Then they removed all the bone "that wasn't formed right," Dr. Hankinson describes.

"It's important that I'm there because that's where you're more likely to have a neurological injury," he adds. "Once that is done, then we try to rotate the spine into a more sustainable, straight position. And then we make decisions about, 'Do we have to put any kind of a cage or graft between the portions of the bone in the front of the spine, or can we just kind of straighten it out and that's going to be good enough?' Then we lock in the alignment and complete the spinal fusion."

"That was a long day," Dr. Garg remembers. "That was very nerve wracking."

"One of the things that's really important is the relationship Sumeet and I have," Dr. Hankinson says. "It's not that easy to have that kind of relationship between orthopedics and neurosurgery. Over time, we sort of recognized where our skill sets are similar and where they are different and how we can benefit the patient."

Rounding out the operation was pediatric plastic surgeon David Khechoyan, MD. He expertly closed the incision, elevating healthier flaps of muscle over the screws and rods to reduce infection and improve the padding.

"I saw Dr. Hankinson and Dr. Garg walking out and they were smiling," Jennifer remembers. "And I was like, 'Ah, okay.' They were laughing together and I'm like —"

"It must have gone well," Jeff finishes.

America's next Ninja Warrior

"Amerrriiicannnnn Ninnnnnjaaaa Warrrriorrrr!" Hunter growls in a deep voice, mimicking the introduction for his favorite TV show. He hangs from the counter in the living room, scrambles across the couch pillows and up the stairs to the kitchen, showing off his ninja moves.

When his mom announces that they're going to the park, he bounds to the door.

After being discharged from the hospital, Hunter spent two weeks at home on his side and stomach. With the help of a private physical therapist, Hunter began to crawl. Then with more help from a physical therapist at Children's Colorado's South Campus whom Hunter calls "Miss Anne-Marie" (Anne-Marie Wilson, PT), he began to stand. Then he began to walk with his walker. And now, he walks on his own, better than before his surgery.

Today, Jeff and Jennifer are helping Hunter with his jumping skills.

"I want him to keep up with the kids that he's playing with," Jeff says. "I want him to beat, bang and bash all over the playground. I want the rough and tumble. He's a little boy and he's climbing all over stuff and he's just having a blast."

"Being able to see Hunter with his peers and some of them are bigger than him and some of them are a little rougher," Jennifer says. "But just allowing him to be him and not intervene. That's been my big thing, so that he can take care of himself in these situations."

"He's just so amazing and has pushed through and he's such a champ," Jeff adds. "I'm thinking to myself, 'I never thought at my age my hero would be a 3-year-old.'"

Featured Researchers

Sumeet Garg, MD

Pediatric orthopedic surgeon

The Orthopedics Institute

Children's Hospital Colorado

Associate professor

Orthopedics

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Todd Hankinson, MD

Division Head

Pediatric Neurosurgery

Children's Hospital Colorado

Professor of Neurosurgery and Pediatrics

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Molly Buerk, PA-C

Physician assistant

The Orthopedics Institute

Children’s Hospital Colorado

Instructor

Orthopedics

University of Colorado School of Medicine

David Khechoyan, MD

Pediatric plastic and craniomaxillofacial surgeon

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

Children's Hospital Colorado

Associate professor

Surgery-Plastic/Reconstructive

University of Colorado School of Medicine

720-777-0123

720-777-0123