- Doctors & Departments

-

Conditions & Advice

- Overview

- Conditions and Symptoms

- Symptom Checker

- Parent Resources

- The Connection Journey

- Calm A Crying Baby

- Sports Articles

- Dosage Tables

- Baby Guide

-

Your Visit

- Overview

- Prepare for Your Visit

- Your Overnight Stay

- Send a Cheer Card

- Family and Patient Resources

- Patient Cost Estimate

- Insurance and Financial Resources

- Online Bill Pay

- Medical Records

- Policies and Procedures

- We Ask Because We Care

Click to find the locations nearest youFind locations by region

See all locations -

Community

- Overview

- Addressing the Youth Mental Health Crisis

- Calendar of Events

- Child Health Advocacy

- Community Health

- Community Partners

- Corporate Relations

- Global Health

- Patient Advocacy

- Patient Stories

- Pediatric Affiliations

- Support Children’s Colorado

- Specialty Outreach Clinics

Your Support Matters

Upcoming Events

Colorado Hospitals Substance Exposed Newborn Quality Improvement Collaborative CHoSEN Conference (Hybrid)

Monday, April 29, 2024The CHoSEN Collaborative is an effort to increase consistency in...

-

Research & Innovation

- Overview

- Pediatric Clinical Trials

- Q: Pediatric Health Advances

- Discoveries and Milestones

- Training and Internships

- Academic Affiliation

- Investigator Resources

- Funding Opportunities

- Center For Innovation

- Support Our Research

- Research Areas

It starts with a Q:

For the latest cutting-edge research, innovative collaborations and remarkable discoveries in child health, read stories from across all our areas of study in Q: Advances and Answers in Pediatric Health.

Anesthesia and Sedatives in Young Children: FDA's Warning Regarding Possible Adverse Developmental Outcomes

Written by Gina Whitney, MD

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently issued a statement on sedatives, general anesthesia and brain development in young children. The FDA warns that in children less than 3 years old, long anesthetics or use of sedatives (which they define as lasting more than three hours) may be linked to problems in neurodevelopment. These problems may also be related to having two or more anesthetics. General anesthesia or sedation lasting one hour or less, or general anesthesia in older children are not suspected of causing problems.

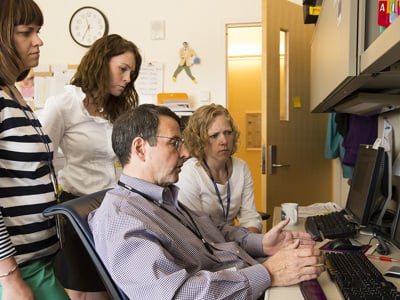

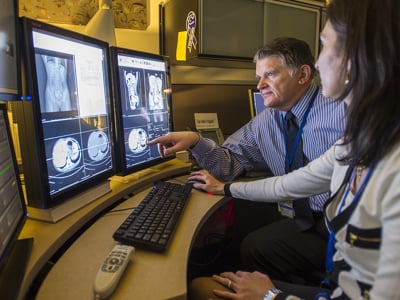

Pediatric anesthesiologists at Children's Hospital Colorado are available to offer advice about referring young children for anesthesia or sedation to help primary care providers explain the issue to your patients' parents. Our team is available any time for consultation with you or your patients' parents about these issues.

What is the background and preclinical data that led to a concern?

Questions about possible effects of general anesthesia on neurodevelopment stem from several series of animal studies that showed an increase in apoptosis (programmed cell death) in various regions of the brains of animals exposed to long-duration general anesthesia and/or sedation. These studies also showed long-term decrements in learning and performance as animals grew to adulthood. Although researchers performed the initial studies in rodent models, they have seen similar results in non-human primate models. It should be noted that the anesthetics in these models, like many animal models of drug toxicity, used equipotent doses to those employed for human anesthesia or sedation, but long exposure times.

Have similar results been seen in human studies?

Yes and no. Several retrospective studies of large cohorts of patients have found decrements in various measures of learning and school performance, while others have not. The reasons for the disparity of the results are unclear, but like all retrospective studies, confounding and unmeasured variables often lead to different outcomes. Furthermore, differences in the measurement of neurodevelopmental outcomes can result in conflicting conclusions. Nevertheless, studies with positive results suggest that multiple or prolonged exposures may be associated with adverse outcomes, while single, brief exposures are not.

The best and only prospective randomized data to date on brief exposures (averaging one hour), which comprise more than half of anesthetics in this age group, come from the GAS trial where infants were randomized to general or spinal anesthesia for hernia repair. This study showed no difference in cognitive performance at 2 years of age between groups; the final results at 5 years of age are still pending. The PANDA study, using a non-randomized sibling cohort methodology, had similar findings over a longer follow-up period.

Neither of these studies were designed to measure neurodevelopmental outcomes following prolonged (> 3 hours) general anesthesia exposures, so the primary question raised by the animal studies remains unanswered in humans. This has obvious implications not only for long operations or diagnostic studies performed under general anesthesia, but even more so for prolonged sedation in the intensive care unit, which may last for weeks, not hours.

If animal and retrospective studies are applicable to my patient, are there ways to mitigate the problem?

In some cases, perhaps. If we assume that the duration and total dose of general anesthesia or sedative is related to the risk, in some cases we can use lower doses of general anesthesia by combining it with other techniques (such as a regional anesthetic or more opioid). For some operations, of course, this is not possible. Some of these potential detrimental neurodevelopmental effects may be mitigated by nurturing educational, environmental and social-emotional enrichment activities. These activities have been shown to exert a protective effect on neurodevelopmental outcomes in one animal study.

Should an operation or study requiring anesthesia or sedation be postponed until a child is older?

It depends. Certainly, it is prudent not to order procedures or tests that are not essential for an infant or young child's health. However, the primary consideration should always be the necessity of the procedure, or whether the information from the study will significantly affect the therapeutic decisions necessary to care for the child's condition.

Neither the FDA nor Children's Colorado are suggesting that essential procedures be postponed, but rather that a careful analysis be made of the benefits and potential risks before scheduling an operation, procedure or diagnostic study. When such an analysis suggests that little therapeutic or diagnostic benefit would result, it is most prudent to wait on the procedure until the child is older. But if a procedure or test is needed, it should absolutely proceed because such a need outweighs the potential consideration of the anesthetic's effect on learning in the future. Furthermore, there are data that suggest that inadequate anesthesia, pain or sedation also may have adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, so if a procedure is indicated, anesthesiologists must provide appropriate levels of sedation and analgesia.

What should I tell my patients?

There are risks and benefits to any medical intervention. The use of general anesthesia or sedation adds an additional consideration when considering the risks and benefits of any procedure or operation. SmartTots provides information about this issue for both the lay public and professionals, and it has links to some of the current research. SmartTots is a public-private partnership research initiative between the FDA and International Anesthesia Research Society.

Where can I get more information?

Contact the Children's Colorado anesthesia team for consultation or with any questions at 720-778-5337. Several Children's Colorado faculty are actively engaged in research on this important topic. Children's Colorado is a primary site of the GAS trial and our Chief of Anesthesiology, Randall Clark, MD, is in the forefront of basic science research on this topic.

Sources:

- Ing C, Rauh VA, Warner DO, Sun LS. What Next After GAS and PANDA? Journal of Neurosurgical Anesthesiology 2016;28:381–3.

- Davidson A. The effect of anaesthesia on the infant brain. Early Human Development 2016.

- Davidson AJ, Becke K, de Graaff J, Giribaldi G, Habre W, Hansen T, Hunt RW, Ing C, Loepke A, McCann ME, Ormond GD, Pini Prato A, Salvo I, Sun L, Vutskits L, Walker S, Disma N. Anesthesia and the developing brain: a way forward for clinical research. Pediatric Anesthesia 2015;25:447–52.

- Nemergut ME, Aganga D, Flick RP. Anesthetic neurotoxicity: what to tell the parents? Pediatric Anesthesia 2014;24:120–6.

- Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Functional implications of an early exposure to general anesthesia: are we changing the behavior of our children? Mol Neurobiol 2013;48:288–93.

- Vutskits L, Davis PJ, Hansen TG. Anesthetics and the developing brain: time for a change in practice? A pro/con debate. Pediatric Anesthesia 2012;22:973–80.

720-777-0123

720-777-0123